John* was in for another scan after experiencing chest pain. Having had a pulmonary embolism about six years ago, he knew the symptoms and what they meant – a trip to the emergency department. His treatment followed the guidelines perfectly: a rapid and timely assessment by the team, D-dimer tests and a CT pulmonary angiogram. But when the scan came back, it was clear of clots.

This had been John’s seventh such scan in an 18-month period and he was already on anticoagulants. He had a history of depression with anxiety and an awful lot going on at home. Chest pains happen for all sorts of reasons, so why did the team put him through scans that were difficult, unnecessary and in the end didn’t address the problem?

With hindsight, it is very easy to criticise the decisions that were made, particularly considering the scan came back clear. But what else could the team have done to make better decisions, better use of resources and ensure a better outcome for the patient? Experience tells us that patients rarely have just one problem. So how do you find a way to connect with them during complex cases like this when there are multiple guidelines and options and no single answer seems right? This is what shared decision making (SDM), as part of Realistic Medicine, is designed to do – to put the patient and their experiences at the centre of their care.

When you have met many hundreds of people with thrombosis, it’s easy to forget how that experience translates into a relatively easy conversation that enables you and the patient to jointly assess the right course of treatment for them. I wanted to share a few tips that have helped me have such conversations to support SDM. You may just have 10 minutes, you might have an hour, but you can still use this advice or use it to guide a colleague.

Get to know the person in front of you

Differences in patients’ ages and past experiences can mean huge variation in how they present with the same symptoms. Some people are risk averse, some catastrophise and others may be thinking only about a work or holiday date. It is important to really understand what drives the person in front of you: it changes plans, and helps make decisions and sets priorities.

Asking about their job, who else is at home and what they do to relax might seem like small talk but only take a moment and will help you and your patient understand each other and build trust. If the patient does not trust you they may feel you are making decisions for them rather than with them. Knowing what is important to your patient and their personal circumstances will help you both navigate through difficult options.

Go through the options – in a way they can understand and trust

Everyone comes to a consultation with different expectations, experiences, knowledge, biases and assumptions. You have them too, so be self-aware. What you are aiming to do is bring together your expertise with the patient’s own experiences of their illness and themselves. You want to develop a plan or treatment that works and serves the patient’s needs best, so keep bringing things back to them and their priorities.

When you mention a diagnosis or treatment, remember that what may seem like a small word to you can sound earth shattering to your patient. Consider body language, watch their face, and be alert to your own feelings and emotions as you talk. Do not hide behind euphemisms (especially if you are talking about death or dying) and don’t be inappropriately blunt. This a person you are speaking to – be kind and be human.

Check your understanding of what the patient is saying. Explore, reframe and reflect answers all the time. When you talk about risks, be very clear: talk about absolute risk rather than relative risk when you can. Rather than asking ‘do you have any questions?‘ ask ‘what questions do you have?’ Check your patient understands, answer all their questions and take time when you need to.

Use health coaching to help make decisions and plans

You can go on a course to really learn how to be a health coach, but there are some easy things to get you started. Coaching is about having the right type of conversation using a certain style of question. It doesn’t tell people what to do but explores how they can do it. A health coach supplies information, perspectives and gives feedback – they look at what’s stopping things changing.

If you start asking things in a different way, you get different answers. I have a few examples that I have found helpful:

- What have you tried so far to help? You will learn far more about what is really bothering them. It’s also quite a positive statement showing your intent to improve the situation with them.

- What else have you considered… and what else? Don’t feel the need to fill every pause. Spending time listening is good and in learning their history you will get a much more complete picture.

- What is stopping you from trying that? This is a very powerful coaching question. In his book, The Inner Game, Tim Gallwey wrote a formula: ‘Performance equals potential minus interference’. By finding out what is in the way of achieving a goal – be it skills, knowledge, support, time, resources or confidence – you know where to focus your support.

- How would you know it has worked? or what would other people notice if you were feeling better? These sorts of questions can help someone see things from a different perspective, focusing on the future and what is really bothering them. This also gives you something to measure improvements against as time goes by.

- What would your best friend tell you to do? This shifts perspective and may motivate a more positive commitment to the treatment plan. Coaching is only as effective as the patient putting it into effect.

Get a commitment

You both need to be clear on exactly what you have agreed to do, so summarise and check the detail. When are you going to do things, who is going to do it, how will you know it has been done? I have found that getting this down on paper is very powerful, so document it and share that agreement with each other so it can be something you look at next time. Make it clear that this can be amended by the patient at any time without prejudice. Views and decisions often change as more information becomes available or treatments are tried.

Creating a culture that supports shared decision making

We all have a role in this, whether you run the hospital or the blood count analysers. It is important to think how everyone in the team can promote shared decision making and patient self-care. As pathologists, we are perfectly placed to guide on how tests are used in just the same way as radiologists police the use of X-rays. Many of us will be in direct contact with patients, but we all have a deep understanding of false positive, false negative and diagnostic uncertainty and should share this knowledge.

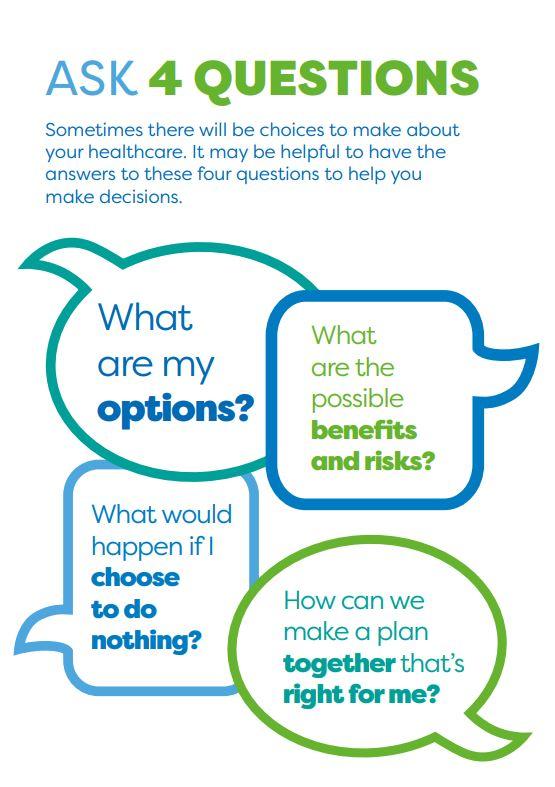

Make sure you discuss and consistently demonstrate what you want to achieve. You can train people, write policies differently, provide access to good information or create campaigns to raise awareness. As an example, this simple poster is above every desk in the outpatient department of Northumbria Trust and is also sent to patients before they attend for their appointment.

What we have observed is that patients are more likely to ask about their options. They arrive more prepared for their consultation and ask about what would happen if we just do nothing. We have also noticed that the poster helps prompt clinicians too. It provides a nice reminder of the framework of shared decision making.

What always works best is when you work with someone to find the solution that suits them, that fits in with their life, their values and their goals. That’s all you need to remember when it comes to shared decision making this is about your patient. Medicine is complicated, choices are hugely varied and guidelines numerous. We learn what works, we learn what doesn’t and most of all we get to hear the stories. Talk to people, listen and invest your time in them. When you get shared decision making right it will save you time and resources, because it saves the patient’s time and resources too.

*name changed for patient anonymity