The view from the RCPath: Dr Rachael Liebmann

Some extended roles for scientists have been developed in histopathology in recent years, primarily in the fields of cytology and molecular pathology. In these roles, clinical cytologists and molecular clinical scientists undertake clinical responsibilities, replacing some of the activity and functions that has been previously carried out by consultant medical staff. In addition, scientists have been training to undertake macroscopic dissection of pathological tissue specimens for several years including obtaining additional qualifications and expertise.

However, unlike in other pathology specialties, there has been no formal clinical scientist training programme in histopathology. Workforce data from the NHS Information Centre (2011) identified only a total of 17 consultant clinical scientists in cytology and histopathology. The microscopic aspects of diagnostic histopathology continue to be provided almost entirely by medically qualified individuals at consultant grade and junior doctors are tasked with the prescreening of cases but with limited introduction of graded responsibility.

In most departments, all slides of all cases, even normal biopsies, are looked at by the supervising consultant prior to the report being signed out. This means that in many histopathology departments there are large backlogs of reporting work, accompanied by frustrated biomedical scientists unable to help. Some years ago, this situation occurred in cervical screening cytology, as most consultants had huge heaps of unreported cervical cytology in their offices.

The College felt that it was important to address this, while not forgetting that many consultant histopathologists feel strongly that only medically qualified consultants can report histopathology. The College’s ‘corporate memory’ is long, however, and this was also the prevailing opinion among a large number of consultant histopathologists about cervical screening cytology 20 years ago. The pilot began in earnest in 2010, having been discussed at a high level between the Department of Health, the IBMS and the College for some years before this.

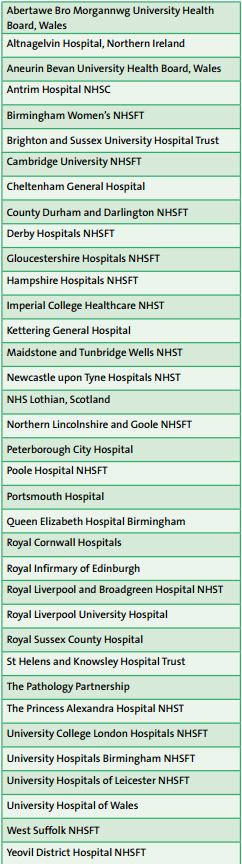

The Biomedical Scientist Histopathology Reporting Pilot Project expanded in its second and third years, with enthusiastic participants in cellular pathology departments throughout England, Scotland and Northern Ireland (listed in Table 1). The Pilot Board were able to stand on the shoulders of the ophthalmology training programme, which had been in place for some years before we began. The RCPath curriculum for the histopathology ST1 trainees lent itself to amendments that allowed a focus on two areas at this stage: gastrointestinal and gynaecological pathology. These were chosen as they represent areas of histopathology practice with a high volume of low-complexity, low-litigation reporting, and which frequently contribute to departmental reporting backlogs.

The pilot participants and their supervisors together made the pilot a huge success. However, managing a training programme for ST1 histopathology trainees is a very different experience to managing a unique pilot, for which the participants have to find time over and above their normal remunerated activity. All of the pilot participants are senior BMSs and most, but not all, are already advanced practitioners in cervical cytology or advanced dissection practitioners. In addition, many of the pilot participants have managerial responsibilities in their employing organisations, business cases to write and reconfigurations to manage.

All of the participants showed great dedication to acquiring new skills and experience and in taking on board the wider clinical aspects of histopathology practice. The degree of challenge should not be underestimated, since the bulk of the macroscopic examination and histologic reporting experience has to be acquired in addition to the ‘day job’. It is not surprising that some participants have been struggling to stay on track with the pace of learning and chose to defer the date of the College examination to allow further apprenticeship learning and double-headed histopathology reporting experience.

The main learning for the College throughout the pilot was that if new skills and experience are to be gained by such senior individuals, over and above their normal employment, this would happen at a different pace for each individual. The College could not afford to have unrealistic expectations. The Conjoint Board qualifications already established in histopathology are clearly understood by pathologists and scientists alike and the Ophthalmology Conjoint Board was a success.

Table 1: Departments with pilot participants

The way forward

Both the RCPath and the IBMS decided that it would be sensible to establish a Conjoint Board for Biomedical Scientist Reporting of Histopathology in gastrointestinal and gynaecological pathology. The proposal was approved by the SAC on Cellular Pathology and the College’s Head of Educational Standards, and the College’s Trustees approved it in July 2014.

The Conjoint Board will be a joint Board of the IBMS and the RCPath to oversee and further develop the work which to date has been undertaken by the RCPath BMS Histopathology Reporting Pilot Board and further advance the practice of biomedical scientists in histopathology reporting. The Board will be responsible for the training strategy comprising the development of the curriculum, learning outcomes and examination of histopathology BMSs. The Board will report progress through the IBMS and RCPath Councils. As the Chair of the Pilot Board, I am delighted to be able to pass a successful pilot over to this tried and tested process. However, I am keen that equivalence of all of the Conjoint Board qualifications in cellular pathology are worked through so that Modernising Scientific Careers will encompass these clearly.

The view from the IBMS: Nick Kirk

The practice of medicine has always been an evolutionary process, interspersed with intermittent flashes of revolution in practice. However, even those revolutionary flashes take on an evolutionary pathway after a while. This is certainly the case in pathology, where sudden scientific developments have led to rapid changes in practice, which then become embedded and then assume a slower pace.

This applies equally to how we use our staff and how we use technology. This was ably stated by Rudolf Virchow, one of the great pioneers of pathology in the 1880s: “If we would serve science, we must extend her limits, not only as far as our own knowledge is concerned, but in the estimation of others”.

The history of histopathology demonstrates this maxim very well. In recent years, we have seen the establishment, development and implementation of a training programme for BMSs in specimen dissection, an area once the sole proviso of the histopathologist. With the increasing demands being placed on histopathology services, both in terms of staffing and financial resources, it was clear that the more traditional practice had to evolve into something new.

This programme was developed in collaboration between the RCPath and the IBMS, which led to the formation of a Conjoint Board to oversee the development of the curriculum and assessment method. We now have a very well-established and respected programme, producing highly skilled and motivated BMS staff, who work alongside their consultant histopathologist colleagues.

It has now further evolved, again with collaboration between the two professional bodies into an advanced specialist qualification in ophthalmic pathology and breast and lower GI specimen dissection. So what next? Was there going to be evolution or revolution? I would like to think that the development of the BMS histology reporting pilot was more of a natural evolution of the specimen dissection programme than necessarily a revolutionary one.

The pilot programme followed the same evolutionary process, with a collaborative project to determine the scope of practice, curriculum and assessment methodology. Strict acceptance criteria for the programme were set, as ‘only the best would do’, and this has been rigorously followed. We are now into the third intake and the feedback received so far has been nothing but positive. Those undertaking the training have proven themselves to be more than able to meet the learning outcomes of the programme and time after time have demonstrated a very high level of knowledge and practice, whilst maintaining a clear understanding of the limits of their practice. Many doubters of this programme stated that these people would replace consultants or damage the medical training programme. It was the ‘thin end of the wedge’.

This was certainly never the intention. From the outset, the programme was always intended to provide highly skilled and motivated staff who would complement, not replace, existing practice and evidence received so far clearly demonstrates that to be the case. In a time when skill mix plus recruitment and retention problems are a feature in most UK labs, having a programme that offers real opportunities for the development and advancement of BMS staff in histology – something denied them through the Modernising Scientific Careers programme – while at the same time taking some of the pressure off their consultant colleagues is, to my mind, a clear and positive benefit to an individual lab’s ability to deliver a timely and quality service to its patients. This, coupled with the difficulties many Trusts are experiencing in recruiting consultant histopathologists, means this solution makes very good sense. It is a positive evolution and not one to be feared.

The view from a pilot participant: Maria Haynes

I like a good challenge – and this hasn’t disappointed me! I started the pilot in the first group two years ago and I was not sure what to expect. The biggest surprise was the difference in the training pathways and career backgrounds of biomedical scientists (BMSs) and specialty registrars (StRs).

As a BMS you do not have the clinical background of a STr, so there is a lot (really a lot) of background reading and legwork to gain understanding of what exactly the clinician is asking and why. It is not always straightforward and there are layers of information to interpret.

In addition, you obviously have to learn the microscopy and how to write a good report. If you work hard, it will stand you in good stead for the OSPEtype exam at the end of the first year. Don’t be shy to ask questions and read around new things as much as you can. It’s hard to find enough time.

You have to fit the work for the pilot in around your normal job and make sure you have fulfilled your case requirements, together with all your assessments. I think everyone on the scheme has done quite a lot in their own time, making the working day quite long sometimes. However, you do get out what you put in and the results are substantial. It is amazing to realise just how much I have learnt and how much more there is to learn. I feel I have been particularly well supported within our department at Maidstone and as a result the progress I have made and the skills I have developed have been enhanced.

The final year is going to be very busy: the portfolio, practical assessment, exams and a viva – plus the day job! It is difficult to manage sometimes and there is a lot of work to do, but it is totally worth the effort. I feel sure that successful graduates of the pilot scheme and the subsequent training programme will be a valuable adjunct for histopathology consultants in the near future.

The view from an educational supervisor: Dr Jim Carson

I was asked to undertake the role as educational supervisor just over a year ago for a consultant BMS who applied for and was accepted onto the RCPath/ Institute of Biomedical Science (IBMS) BMS reporting pilot. I tentatively agreed, not knowing the full details of what was required, but was of the opinion that this was an important initiative. I could see that it would complement our consultant pathologists’ team in much the same way as the advanced practitioner (AP) role has served in the provision of a cervical cytology service and as specialist nurse practitioners have complemented the clinical services in endoscopy, colposcopy, haematology and respiratory, for example. At my first meeting at the College with the project leads, educational supervisors and candidates, I realised this was a substantial project with a comprehensive syllabus and portfolio requirement, which would involve a considerable amount of work.

I was fortunate, however, ON THE AGENDA 30 January 2015 Number 169 The Bulletin of The Royal College of Pathologists in that ‘my’ trainee was an experienced BMS who has been an AP since 2003. This is an important point. It is a demanding role for the trainee and supervisor and, in my opinion, should only be undertaken by an experienced BMS – either an AP or someone who has obtained an advanced specialist diploma (e.g. in dissection). An AP has the microscopy and independent reporting skills and thus requires a different training programme from those potentially coming from a dissection background. Two modules can be undertaken at the same time: gynaecological and gastrointestinal.

My trainee opted for the gynaecological module only. Both modules would be a very substantial requirement in terms of time and resources. A second important factor in my decision to take on this role was that I had the support of my consultant colleagues. This meant that the trainee was exposed to different reporting styles and a variety of sub-specialty expertise. The candidate also benefits from the pathology trainees and vice versa. It is important the trainee quickly becomes part of the pathologists’ team rota in much the same way as the pathology trainees, and this was achieved by simply adding a column to the weekly team rota headed ‘BMS reporting pilot’. Seeing a wide variety of pathology and signing out with experienced consultant pathologists on a regular basis is fundamental to their training.

Additional dissection training is given by our experienced BMS dissectors – again, an invaluable support. In-house lectures, attendance at gynae multidiscplinary team (MDT) meetings, cervical cytology discrepancy meetings, presentation of audits and clinical case reviews at our monthly governance meetings and mock exams are all part of the training programme. The audit and clinical case review day at the College in June 2014 was very useful and gave a good indication of the high standard the candidates had reached in under one year. This is a time-consuming undertaking but I can already see the potential benefit to a pathology department in coping with an increasing workload year on year. The demanding threeyear programme will require a focused and dedicated approach from the trainee, supervisor and supporting consultant pathologist colleagues. Long-established consultant pathologists like myself will have to become more familiar with the portfolio-based aspect of this programme.

This programme, however, is more than that reqiured for the portfolio-orientated AP and advanced specialist diploma qualifications and hopefully the exam title will reflect the status of this new role. It is a challenging role which I would recommend. It can only strengthen the service we provide.

The view from a specialist scientific lead in ophthalmic pathology: Adam Meeney

The advanced specialist diploma (ASD) took around five years to complete, from being appointed in post until the certificate was issued. I was lucky enough to be recruited into a post as a ‘trainee advanced practitioner’, meaning I was free to concentrate on gaining the experience necessary to pass the exam process.

This did not just involve learning the job role in the laboratory, but also attending the ocular oncology MDT meetings each week, along with visiting clinic and theatre sessions to learn about diagnosis and treatment of ophthalmic disease. It is important to do this as, coming from a BMS background, I have a lot of laboratory knowledge but very little clinical knowledge or experience.

This process also helps forge good relationships with the clinicians for whom you will be providing histology reports, whether they be macro or micro, and this open communication and trust is important for clinicopathological correlation.

After all, the clinicians need to trust your reports once you are compiling and signing them out yourself. In terms of the examination process, this involved the completion of a portfolio of evidence, a workplace cut-up assessment, a written exam, a slide exam and a viva voce.

The examination was a drawn-out experience over a number of months, but I think this was most likely due to it being the first examination process of its kind. It needed to be transparent and accountable, which took time to organise. The most difficult part of the process for me was the slide exam. It was a new experience for me (though I have plenty of experience of written exams and have been doing specimen dissection of one type or another for years) and I found time management difficult. I wasn’t sure whether to tackle the cases I was sure about first and come back to the more difficult ones later or vice versa, and this resulted in a rush towards the end! My advice would be to have a clear game plan before you start and stick to it.

I was obviously very happy when I received my ASD certificate, but this really is only the beginning of the learning process. Practising independently means making clear decisions and trusting your judgement. I think that medical training prepares you much better for this than laboratory experience and learning this skill takes time. Clearly over-confidence is even worse and it is important that your work is properly reviewed and audited, especially when you are at the start of your career.