Introduction

The impact of anaemia occurring in pregnancy and the postpartum period should not be underestimated; it is a public health problem that affects low-, middle- and high-income countries, and has significant adverse consequences, not just on health but also on social and economic development. Furthermore, maternal anaemia is associated with increased risk of maternal and perinatal mortality, irrespective of confounding factors.

The World Health Organization estimated that, worldwide, 38% of pregnant women were anaemic in 2011, equivalent to 32 million pregnant women.1 Iron deficiency accounts for the majority of these cases and is the most common cause of anaemia in the obstetric setting, with additional common causes including genetic red cell disorders, infectious disease and folate deficiency. Data from the UK, where iron is widely available and national guidelines for the management of iron deficiency in pregnancy have been in place since 2012,2 suggest that, where guidelines are adhered to, maternal anaemia is identified promptly and managed appropriately. However, there remain key aspects of prevention and treatment that require greater attention.

Definition of anaemia in pregnancy

The British Society for Haematology defines anaemia in pregnancy as a haemoglobin concentration (Hb) <110 g/L in the first trimester, <105 g/L in the second and third trimesters, and <100 g/L postpartum.3 This definition, which is based on lower Hbs than in non-pregnant women, reflects the differential physiological expansion of red cell mass and plasma volume that occurs in pregnancy; expansion in plasma volume almost doubles that of the red cell mass and results in haemodilution.

Following childbirth, anaemia is associated with fatigue and increased risk of postnatal depression, both of which have been shown to improve following iron supplementation. The risk of sepsis and poor wound healing may also be increased.

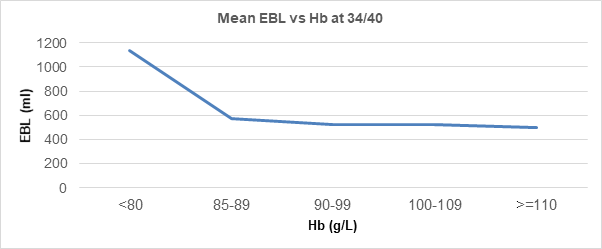

This change begins at around 12 weeks’ gestation and is maximal by the end of the second trimester. The fetal demand for iron and enhanced maternal red cell production significantly increases iron requirements and risk of iron deficiency anaemia, particularly as many women of childbearing age begin pregnancy with reduced iron stores. Untreated antenatal iron depletion may lead to postpartum anaemia, which can also be caused by increased blood loss at delivery, and can be inversely correlated with Hb (Figure 1).

Although the major burden of maternal anaemia is borne by low- and middle-income countries, particularly Sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia, anaemia affects women in every country. In the WHO 2020 Global Nutrition Report, no country was on track to meet the target of a 50% reduction in maternal anaemia by 2025.4 In the UK, an audit of the management of maternal anaemia and iron deficiency carried out by NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) in 2019 found the prevalence of iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy, in some centres, to be as high as 30.4% and 41.3% in the puerperium.5

Why does maternal anaemia matter?

Maternal anaemia has important consequences including symptoms such as fatigue, cardiovascular strain, and thyroid and immune dysfunction. It also increases the likelihood of blood transfusion, with risk of adverse events including red cell alloimmunisation, in turn predisposing the fetus/newborn to haemolytic disease and potentially causing issues around obtaining compatible blood for mother and baby. Maternal anaemia is also associated with low birth weight,6 preterm birth,7 postpartum haemorrhage and increased maternal and perinatal mortality. Following childbirth, anaemia is associated with fatigue and increased risk of postnatal depression,8 both of which have been shown to improve following iron supplementation.9 The risk of sepsis and poor wound healing may also be increased.

UK guidelines

Evidence-based guidelines are in place in the UK to aid prompt diagnosis of maternal anaemia and appropriate treatment.3 These guidelines advise that all pregnant women receive dietary advice to optimise iron intake and that Hb is routinely checked at booking and at 28 weeks’ gestation. If anaemia is diagnosed, a trial of oral iron should be initiated promptly and used as a diagnostic tool, with assessment for Hb response 2–4 weeks later. Counselling in the correct administration is important to aid absorption and minimise side effects; 40–80 mg elemental iron to be taken once daily or on alternate days, early in the morning, with a glass of water or orange juice on an empty stomach, one hour before food, drink or other medications.

It is important to identify those women who are not yet anaemic but are at risk of iron deficiency, for example those with previous anaemia, an interpregnancy interval of less than a year, multiple pregnancy or multiparity. They should either be offered oral iron empirically or have their serum ferritin checked to identify iron depletion. Ferritin should also be checked in women with a known haemoglobinopathy to identify concomitant iron deficiency and exclude iron-loading states.

Intravenous iron should be reserved for anaemic women in the second trimester onwards who have absolute intolerance of or are unresponsive to oral iron, and women presenting after 34 weeks’ gestation with confirmed iron deficiency anaemia and Hb <100 g/L where there is insufficient remaining time before delivery for correction of anaemia with oral iron (Table 1). Women at risk of postpartum anaemia because of blood loss >500 ml, uncorrected antenatal anaemia <105 g/L or symptoms consistent with anaemia should have their Hb checked within 48 hours of delivery. If anaemia is confirmed, iron replacement with oral or intravenous iron should be implemented unless there is cardiovascular compromise and blood transfusion is considered instead (Table 1).

| Table 1: Treatments for iron deficiency anemia. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Antenatal indications | Postnatal indications |

| Oral iron | Low Hb – used as a diagnostic trial and continued if response is seen OR non-anaemic but identified as being at high risk of iron deficiency |

Haemodynamically stable AND mild/no symptoms |

| Intravenous iron | Intolerant or non-compliant with oral iron Hb <100 g/L and 34 or more weeks’ gestation |

Intolerant of oral iron OR severe symptoms |

| Red blood cell transfusion |

Bleeding OR severe anaemia not related to iron deficiency | Continued bleeding or risk of further bleeding OR haemodynamic instability OR symptoms requiring urgent correction |

| Hb: Haemoglobin. | ||

Gap between guidelines and practice: the importance of audit

Despite these clear recommendations, a national comparative audit in the UK carried out by NHSBT in 2019 raised concerns around the management of maternal anaemia and iron deficiency with variable implementation of guidelines.5 In the 86 centres that were studied, involving 860 births, only half of the women diagnosed with anaemia in the first trimester were commenced on oral iron therapy, falling to 30% of women diagnosed with anaemia at 28 weeks’ gestation.

The prevalence of anaemia is higher in low-income countries where contributing factors such as haemoglobinopathies and infectious disease are more common, but iron deficiency remains the most common cause of maternal anaemia

globally and in developed countries.

By contrast, local audit data from Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, where guidelines and pathways for the management of maternal anaemia have been in place for the past seven years, showed that of 7,402 women, 2% were anaemic at booking, 12% at 28 weeks’ gestation and 11% at 34 weeks’ gestation (Table 2). While these values compare favourably with the NHSBT audit, the rise in incidence between booking and 28 weeks is reflective of the large number of women with non-anaemic iron depletion who would benefit from empirical iron given at their booking appointment.

| Table 2: Numbers and rates of antenatal anaemia at Oxford University Hospitals, 2018 (n=7,402). | |||||

| Stage of pregnancy Hb level tested |

n | Mean Hb g/L (range) |

Median | No of pts anaemic (Hb <110 booking, Hb <105 2nd/3rd TM, Hb <100 PP) |

% anaemic of those tested |

| At booking appointment | 4,886 | 128.7 (62−174) | 129 | 110 | 2.3 |

| 28/40 | 6,313 | 115.2 (52−149) | 115 | 790 | 12.5 |

| 34/40 | 6,322 | 115.6 (73-156) | 115 | 696 | 11.0 |

| Pre-delivery | 4,232 | 121.4 (51-225) | 122 | 278 | 6.4 |

| Hb: Haemoglobin; PP: Postpartum; pts: Patients; TM: Trimester. | |||||

An audit of postpartum anaemia in the same centre in 2020 showed that 87% of women at risk of postpartum anaemia had their Hb checked within 48 hours of delivery, with 93% of those diagnosed with anaemia and eligible for treatment with iron replacement receiving it (Table 3). This is an improvement on the national audit data, which found only 78% of women diagnosed with postpartum anaemia received iron replacement.

| Table 3: Results of a single centre audit of postpartum anaemia. | ||

|---|---|---|

| All patients | n=138 | Hb checked |

| Indication for postnatal Hb check | 60 (43%) | Yes: 52 (87%) No: 8 (13%) |

| No indication for postnatal Hb check | 78 (57%) | |

| All postpartum anaemia | n=32 | |

| Treated | 29 (90%) | |

| Not treated | 3 (10%) | |

| Indicated treatment | Received indicated treatment | |

| Iron (oral or IV) | 29 (91%) | 27 (93%) |

| Blood transfusion | 2 (6%) | 2 (100%) |

| Unclear from documentation | 1 (3%) | |

| Hb: Haemoglobin; IV: Intravenous. | ||

Summary and conclusions

Reducing maternal anaemia is a priority for the health of women and children across the world. The prevalence of anaemia is higher in low-income countries where contributing factors such as haemoglobinopathies and infectious disease are more common, but iron deficiency remains the most common cause of maternal anaemia

globally and in developed countries. Disappointingly, 30.4% of pregnant women in certain UK centres were diagnosed with iron deficiency anaemia in 2019, despite the ready availability and effectiveness of oral iron replacement. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of maternal anaemia have been available for many years, and the positive audit data from Oxford confirms the importance of adherence to these guidelines if the prevalence of maternal anaemia is to be reduced and maternal and child health improved.