Background to population screening programmes

Population screening has frequently been in the news and debated over recent months owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. The questions of who, when, why, how and if screening should happen have made headlines far more than I can ever recall. The cost and benefits, the upsides and downsides, and what type of test and technology used are now common conversations.

COVID has brought into sharp relief the difficulties of introducing population screening when there is little to no real data on nearly all these areas, and any that does exist is being produced in real time. The issues thrown up by the COVID screening debate is in sharp contrast to the evidence-based approach of the existing mass population screening programmes in the UK.

The questions of who, when, why, how and if screening should happen have made headlines far more than I can ever recall.

Population screening in this country is overseen by the UK National Screening Committee (NSC). The NSC is an independent body that:1

- advises ministers and the NHS in the four constituent UK countries about all aspects of screening, including the case for introducing new population screening programmes and for continuing, modifying or withdrawing existing population programmes against a set of internationally recognised criteria

- supports implementation of screening programmes in the four countries including the development of high-level standards and maintains oversight of the evidence relating to the balance of good and harm as well as the overall cost-effectiveness of existing programmes

- works with partners to ensure it keeps abreast of scientific developments in screening, including screening trials, screening policy in other countries and emerging technologies.

The NSC uses a rigorous approach to data collection, use, analysis and interpretation. Where evidence is lacking it will identify what is required and look for, or, if needs be, seek to actively obtain such data. Its approach and decision-making are transparent and involve proactive as well as passive consultation from professionals, relevant bodies, charities, the public and those affected by the area of interest. This does not happen by luck. It is a managed, proactive and professional approach. Not everyone agrees with the decisions reached, and in some areas there can be very vocal and well-organised opposition to such decisions.

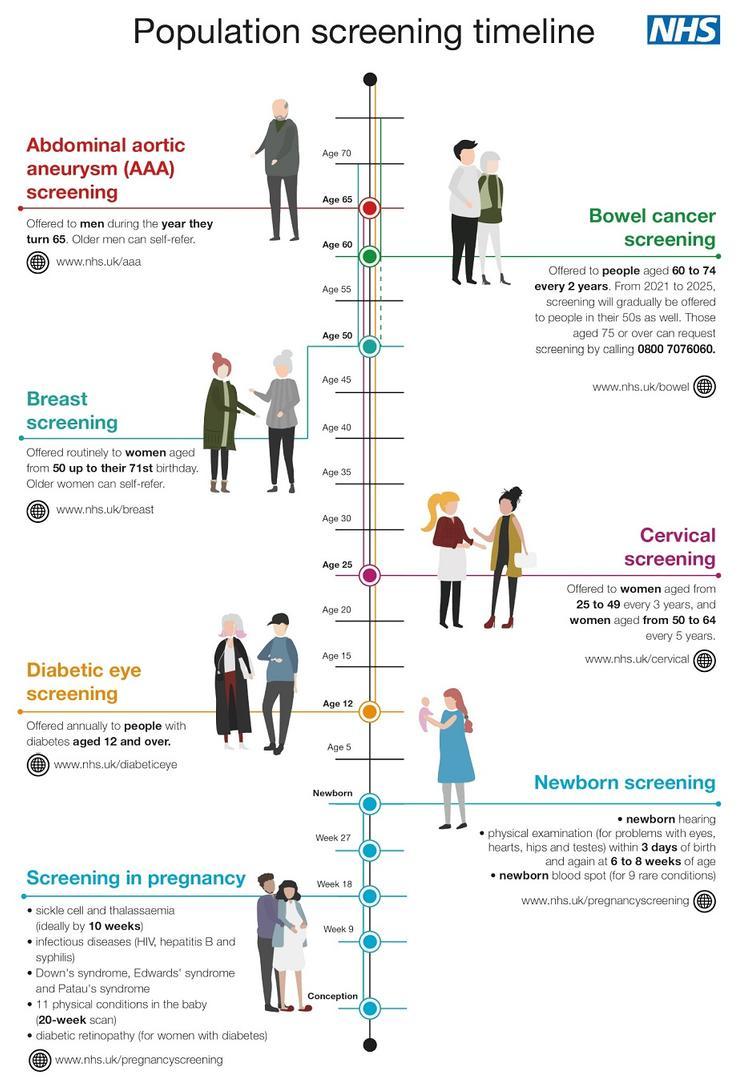

The NSC website lists 11 population screening programmes adopted across the UK, of which three are cancer related.2 These are ones for breast, colorectal and cervical cancers. The aim of cancer screening is to try and detect the pre-cancerous stages rather than cancer per se, although screening will identify cancers also. If a cancer is screen-detected, it is often early stage, more responsive to treatment and with a greater likelihood of cure.

UK cervical screening programme

Cervical screening in the UK goes back to the early 1960s, but it was not until 1988 that it became more organised in England with the development and introduction of a computerised call/recall system. This computer system was used to invite and track women and their screening status and follow up. Using IT systems declared as ‘hopeless’, it has, despite many issues, carried on working with many sticking plasters until now.3 A new system is planned for implementation later in 2021.

The success of the cervical screening programme ... in the UK is obvious, with the rate of cervical cancer having reduced by 25% since the early 1990s.

The success of the cervical screening programme (CSP) in the UK is obvious, with the rate of cervical cancer having reduced by 25% since the early 1990s. While cervical screening is estimated to save 5,000 lives a year, thereby preventing a perceived cervical cancer epidemic,4 there are still some 3,000 cases of cervical cancer diagnosed every year in the UK.5 This is still far too high, and audits of the screening histories of women who develop cervical cancer often show patchy or no screening, less attendance for treatment and that it is more common in women with lower socio-economic backgrounds.6 Much has and is being done to encourage women to attend their cervical screening invitation, including now the trialling of self-sampling to help increase coverage.7

Changes in delivery of cervical screening

How cervical screening is delivered has changed dramatically over the years. At its outset, it used the cervical cells sampled from the cervical os spread directly from the sampling device onto a glass slide and then fixed and stained. This was the conventional Papanicolaou smear, named after George Papanicolaou, who developed it and devised the stain still used for this (the Pap stain), which is also widely used in diagnostic cytology. The conventional smear was used in the UK until around 2005 when it was replaced after trials in the NHS by the liquid-based cytology technique (LBC). The use of LBC as a technique allowed for testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) and so HPV testing was introduced as a reflex test to samples with abnormal cytology. After further trials, we are now in the current CSP model of delivery which is of primary population testing with an HPV test with reflex cytology which helps guide management. This is now the approach in place across the whole of mainland UK.

The changes in technology have also led to a major reconfiguration in the footprint of those laboratories delivering the CSP. From well over a hundred labs 20–30 years ago, we are now down to only eight in England. This is mirrored in Wales and Scotland as well. This has led to a major shrinkage in the number of laboratory staff working in the CSP. The model of delivery easily shows this. In the pre-primary HPV screening model of only two or three years ago, there were some 3,000,000 women screened, each of whom had a cytology sample. It is roughly the same number now but with only about 15% of this number requiring cytology to be looked at (those screening samples that are HPV positive). This is approximately 450,000 cytology samples: roughly one-sixth.

Cervical screening involves many other elements: the call/recall offices, primary care, colposcopy and histology. All of these must work together to deliver a quality system and ensure that the correct result goes to the women it seeks to serve.

Cervical screening involves many other elements: the call/recall offices, primary care, colposcopy and histology. All of these must work together to deliver a quality system and ensure that the correct result goes to the women it seeks to serve. Like all such multi-dependent systems, not everything works well on occasion. The CSP has a history of high-profile problems, such as those at Inverclyde and Kent and Canterbury, including issues with sample taking, IT and follow-up, many of which have affected women directly. Some were laboratory-based issues, but certainly many were not. To some extent, these are inevitable, but we can work to minimise and learn from them.

I have been lucky enough to work in laboratories, delivering the cytology and histology aspects of the CSP, all my working life. I have also been privileged to be a member of the NSC for over five years. There have been issues relating to the CSP I have been able to contribute to, such as the move to primary HPV testing, which have allowed me to see the rigorous approaches used to decide upon possible programme modifications. The work of the NSC is incredibly broad, and cancer screening, while obviously important, is only part of its remit. The multitude of screening for inherited and metabolic diseases is vast, as is the work for acquired conditions such as aortic aneurysms and diabetic retinopathy. It is not all cancer at NSC meetings. Ethical issues are frequently debated and considered as part of the discussions on screening programmes. We must use the scientific data, but in the context of the society in which we live. The work of the NSC is hugely important and affects the whole population of the UK and, as such, any decisions must be taken properly and with due consideration. I hope we have done so; I think we have done so. The views expressed in this article are my own, and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the NSC.